Asia-Pacific

'Comfort women' historian alarmed

(AFP)

Updated: 2007-03-12 07:17

|

Large Medium Small |

Now, Yoshiaki Yoshimi says he is alarmed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's apparent backtracking on the issue, and accuses the Japanese leader of denying the facts when he said there was no evidence the imperial army coerced so-called "comfort women."

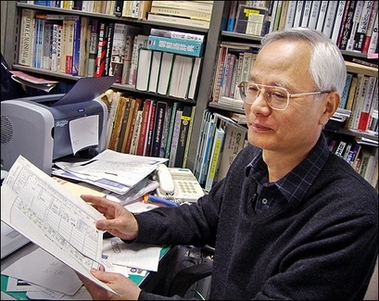

Japanese Chuo University professor Yoshiaki Yoshimi displays an evidence of Japanese troops' involvement in wartime sex slavery two decades ago at his laboratory in Tokyo, 08 March 2007.[AFP] |

Yoshimi, a professor at Tokyo's Chuo University, said he first stumbled upon a document in the 1980s that showed the military issued orders to set up brothels for front line troops.

According to the document, the chief of staff of Japanese troops occupying northern China wanted the brothels to stop soldiers raping Chinese women and stirring up local anger.

Historians believe by the end of the war up to 200,000 women served in brothels for Japanese troops across Asia.

"I was very surprised, because it was one of the first official documents that showed the direct involvement of Japanese authorities," Yoshimi told AFP.

"I knew it was a very important document, so I kept it safe for a few years."

When South Korean former comfort women first came forward in December 1991 to tell their stories, Yoshimi was driven to action.

He went to the library of the Defence Agency, now the Defence Ministry, and after two days of searching found documents proving that the Japanese military was responsible for comfort women.

Yoshimi's research appeared in the influential Asahi Shimbun newspaper on January 11, 1992, and a day later, the government pledged to investigate.

In 1993, the chief government spokesman issued a statement voicing "sincere apologies and remorse" and acknowledging the imperial army was involved "directly or indirectly" in sexual slavery.

But Abe, who is known for his conservative views on history, has promised to assist a new investigation by the ruling party into comfort women -- the first step to a possible revision of the 1993 statement.

"There was no coercion such as kidnappings by the Japanese authorities. There is no reliable testimony that proves kidnapping," Abe said this month.

Abe, while saying he stood by the 1993 apology, argued that economic conditions and sex brokers may have pressured women to work in brothels.

Yoshimi, a silver-haired 60-year-old whose office is crammed with books, quietly decried Abe's remarks.

"It is clear that there was coercion of those women into sexual slavery and it is the Japanese authorities who decided to set up wartime brothels," he said, holding up photocopies of the documents he found.

"The government was the protagonist in this business and brokers were just tools of the government. It was by no means the other way around."

The soft-spoken professor said he has received threatening telephone calls and letters, one reading, "You must die!", since he first published his findings.

Even if the government lets the 1993 statement stand, Yoshimi said, the backlash has taken a toll. He said none of the history textbooks now used by junior high school students make clear reference to "comfort women."

"There is some sentiment that it is impossible to admit wrongdoing. It's a way of asserting cultural self-confidence, especially since the collapse of the bubble economy" in the early 1990s, he said.

Abe's government has furiously rejected a bill before the US Congress, which is more likely to pass since the Democrats took control in January, and which would demand Japan make an outright admission and apology over comfort women.

Yoshimi has signed a petition supporting the bill, saying that Japan's conservative leaders will be more likely to respond to criticism from the US than from China, which frequently spars with Tokyo on history issues.

"I expect the US legislation will be a positive factor in correcting the current conservative backlash in Japan," Yoshimi said. "It's probably impossible for Abe to refuse advice from such an important ally."

Yoshimi hopes to publish a new book with fresh testimony from former comfort women.

"I don't see myself as taking a political role. I see myself as exposing the truth," he said. "Doing this may not always be in the interests of Japan. But that's the role of the historian."

| 分享按鈕 |