Race is on for 'Out of this World' resources

The race to space is on. Perhaps one might say it has been on for years now. However, space exploration, and the launching of new-generation satellites, have been much in the news recently, taking on added significance with important regulatory implications.

Since 1970 when China launched its first satellite, through to sending its first Taikonaut into space in 2003, and landing the Jade Rabbit rover on the moon in 2013, China has become a space exploration superpower and, along with India, it has been making significant inroads towards a capacity to commercialize outer space.

Russia, Kazakhstan, the Ukraine, and Japan have also been active, and, just a few weeks ago, there were calls for Australia to become more proactive in space technology. In Africa, Ghana launched its first satellite GhanaSat-1, heralding the advance of more developing countries into space. In the Mid-East, the UAE is planning to build a city on Mars by 2117.

In general, commercialization of outer space has sometimes led by government; at other times by public private partnerships and most recently has been taken up by major commercial players. In Europe, for example, since 1980 the semi-private firm Arianespace was created and has been active in commercial space launches. However, the cost has generally been prohibitive.

However, the cost of launching pay loads is set to drop with the emergence of new technologies. Elon Musk’s SpaceX has already set the pace by outpricing competitors Arianspace and ULA.

With the launching of its Long March rocket series and plans to complete its first space station in 2020, China has signalled the arrival of affordable, if not cheap commercialization of space and is potentially making it possible for developing countries to launch their own satellites.

Commercial opportunities in space

The attraction of space-based resources is a big incentive. In 2015, the US Congress passed the Space Act which legalized and recognized the rights of American citizens to engage in space mining.

Diverse opportunities abound in this new frontier. In addition to telecommunication satellites and remote sensing, others (e.g. Deep Space Industries with its Prospector-1 mission) focus on resource mining, of nearby asteroids with estimates of trillions of dollars of potential resources on offer.

Entrepreneurs like Britain’s Richard Branson and Virgin Galactic are focusing on space tourism. A surprising number of people have already signed up and committed to travel.

Space-based solar panel farms are also being considered as a way to get cheap and reliable renewable energy for a post-fossil based resource world.

The pharmaceutical industry is also interested in space, for example through its potential for zero-gravity research and testing and possibility of producing products such as improved quality crystals to replace synthesized proteins for the next generation of drugs.

Meanwhile, the advertising industry is already looking for opportunities for branding and other promotions related to outer space exploration.

Yet, major obstacles exist in relation to outer space commercialization. The first one is political. Individual nation states are reluctant to recognize the rights of others in outer space. There is little enforceable law governing this new area of human activity. Understandably, countries are using their space expertise to advance their own agendas.

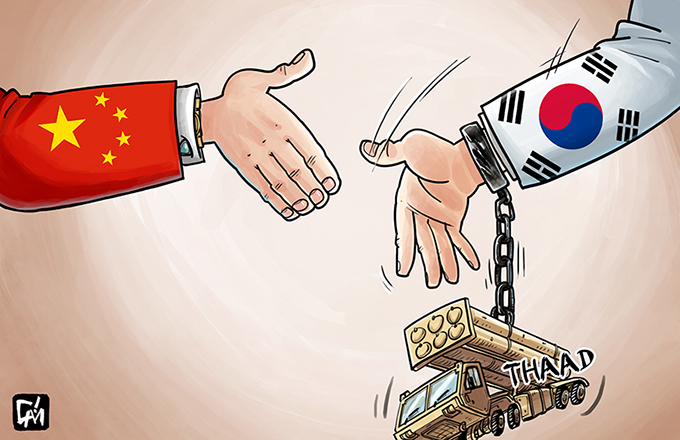

China is using its outer space telecommunications/satellite infrastructure to support all countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiative. Similarly, India is working with the 18th South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) to launch a SAARC satellite to provide communication services free of charge to SAARC members, with the exception of Pakistan which has opted out.

China’s and India’s initiatives show the importance of avoiding a space divide between those nations that have the capacity to exploit outer space and those who don’t.

Absence of an agreed legal framework governing outer space exploration is a big concern. Among the areas needing clarification are property rights, space registration and liability regime, rules governing launching services, telecommunications services, national space legislation and international space cooperation.

Another potential obstacle is the 1967 Outer Space Treaty which provides that no “celestial body” is subject to “national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.”

Quite apart the obvious legal obstacles, space exploration is a risky business and fraught with perils. Commercial players especially require insurance products to manage such risks.

Another challenge is that of space wastes, junk and other debris. Thus far, there are only the Interagency Space Debris Mitigation Coordination Committee Guidelines, endorsed by the UN General Assembly, but remaining voluntary.

Finally, space commercialization efforts require huge sums of capital that have to be advanced for a risky venture. Such capital has never been easy to come by.

By Eugene Clark and Sam Blay