Every five years, the National Congress of the Communist Party of China is held to review the past and to plan the future. China's change has been astonishing. The Chinese people today enjoy higher standards of living, greater freedom of all kinds, and a more vibrant, tolerant society. China's economy is now the world's second-largest; it will likely become the largest, doing in decades what elsewhere took centuries.

But dramatic change causes pervasive problems. Can China achieve its goal of becoming a "moderately well-off society" in a world of turbulent markets and limited resources and in a society of social disparities and structural faults?

This challenge is what China's new leaders face.

China's economic miracle has been driven by investment and exports, both made possible by millions of migrant workers who personify China's most divisive and intractable problem - the economic and social gap between rich and poor, urban and rural, coastal and inland. But must economic development exacerbate social disparities?

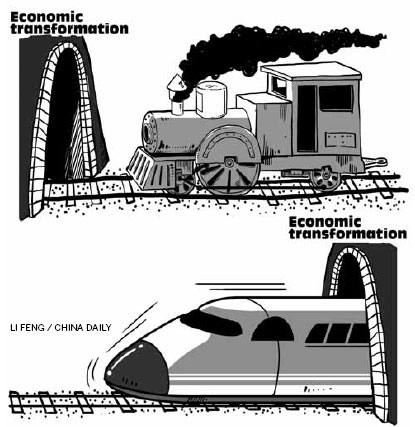

China's growth model - cheap labor, low-cost manufacturing, and energy-intense, high-polluting industry - has come to the end of its historic cycle. China's economy, built of the backs of poor workers, must be transformed. Workers no longer accept low wages, so China's economic model must change or China's economic miracle will end.

How can economic transformation work? Along China's east coast there are many enterprises that began as export engines, enabled by reform and fueled by cheap labor. When the financial crisis crippled overseas markets, many had to close.

The Newcomer Luggage factory in Zhejiang province made low-cost luggage for an international brand. It didn't make much profit and couldn't pay much to workers. But Newcomer changed its business model by creating its own innovative designs and branded products, increasing gross margins from 20-30 percent to 70-80 percent. Salaries of Newcomer workers doubled!

But making innovation work in the marketplace is complex, expensive, uncertain and unpredictable. In short, innovation is risky. Failure rates are very high. So failure must be accepted, or innovation is impossible.

In China, small and medium-sized enterprises, largely private companies, drive the economy, generating about 60 percent of GDP and 50 percent of tax revenues, and providing 80 percent of urban jobs. Nonetheless, policies continue to favor State-owned enterprises, particularly with respect to financing. Less than 15 percent of bank loans go to SMEs.

How can SMEs finance their business cycles? Driven by necessity, an informal system of mutual local financing developed - a private capital chain, not legal, but not quite illegal either. The government didn't much like the gray-market financing scheme, but didn't stop it.

Henglong Small-loan Company in Wenzhou, the center of entrepreneurship in China, lends to small and micro agricultural enterprises - in total, more than 4 billion yuan ($630 million). Henglong can set market-driven interest rates up to three times higher than what banks offer. (But to SMEs, "what banks offer" doesn't mean much because banks won't lend much.)

In 2012, State Council set up a pilot financial zone in Wenzhou, legalizing small loan companies.

If financial reform in Wenzhou affects private business, financial reform in Shanghai affects China's entire economy. Can Shanghai become a world financial center? I ask Fang Xinghai, director of the Shanghai Finance Office. "Shanghai serves a continental-sized economy, and we want to be New York and London," he says. "Let's imagine China's economy reaching the size of the US economy, the yuan becoming a fully convertible currency, and China's domestic financial market becoming fully open, then Shanghai can be at the same level as New York."

If finance is the blood stream of China's economy, manufacturing is its muscle. But for China to continue to grow, it must transform its manufacturing, with technology and know-how.

For example, before 2005, all marine crankshafts for shipbuilding in China were imported. Then the government established Shanghai Marine Crankshaft Company so the country could build ships entirely by itself. Although declining world markets cause losses, the State provides subsidies. What's more, China's political leaders come to give personal support.

Other business models are taking root in China, where State ownership and domestic manufacturing are not primary. Sany is China's largest heavy machinery manufacturer and is built on the twin pillars of private ownership and global expansion. Sany misses no opportunity to enlarge its global footprint. When the copper-gold mine in Chile collapsed in 2010, Sany sent a crawler crane to help with the rescue. When the massive earthquake hit Japan in 2011 and the nuclear reactors leaked, Sany sent a huge concrete pump truck to help cool them down. In 2012, Sany bought a German company and shook up the industry.

When going abroad, though, smooth sailing is not the norm and several Chinese acquisitions have lost money. But the pace continues. In 2010, Geely Automobile purchased Volvo.

Economic growth has a downside - pollution. Environmental damage is the scourge of China, and how to balance economic growth and environmental protection is a major challenge.

The Institute of Public Environment collects environmental data from across China, compiling a database with about 100,000 pollution statistics. With others, IPE launched "Green Choice" to encourage or coerce multinational companies to make their supply chain greener by monitoring their suppliers' pollution. Included are GM, Nike, Walmart and Coca-Cola.

There are cases where activists have forced polluting factories to move. After the government announced plans for a massive $9 billion petrochemical plant in the wetlands of Nansha in Guangzhou, some people began to protest. Few took them seriously and it seemed a wildly uneven battle. On one side was the Chinese government, central and provincial; Sinopec, China's largest oil company; and Kuwait Petroleum, one of the world's largest oil companies. On the other side, a few professors, students, citizen activists. And because economic development is vital, even negative environmental impact would likely be ignored.

But not this time. After a protracted battle, the project departed Nansha. It was a shocking win for environmentalists.

China's new leaders know they face the challenge of continuing to improve the lives of the Chinese people. The Chinese people know it too.

The author is an international corporate strategist and investment banker. He is the author of The Man Who Changed China: The Life and Legacy of Jiang Zemin and How China's Leaders Think (featuring China's new leaders).