Paintings explore odyssey of vision

Sincere creativity

With his subtle brush, Chang Shuhong recorded the Mogao Caves and the Dunhuang city in different seasons: the trees and blossoms in spring; the frozen Daquan River in front of the caves during winter, children playing on ice, a white stupa in the distance; and birds in snow against the backdrop of the landmark timber-structured nine-floor building that houses the tallest statue of Maitreya Buddha, or the Buddha of the Future, at the Mogao Caves.

Upon his arrival, Chang Shuhong and colleagues pioneered a systematic conservation of the relics, planting trees and building protective walls, reinforcing the cliffs, constructing pathways, cleaning up the caves buried in sand, investigating and numbering them. Many of his paintings feature these efforts carried out at the windy and sandy Gobi Desert.

He also depicted several times the bustling temple fair in front of the caves, falling annually around the eighth day of the fourth month on the Chinese lunar calendar, in celebration of the birthday of Siddhartha Gautama (better known as the Buddha).

During the nine years in France, Chang Shuhong focused mainly on classical realistic oil painting, constantly exploring what could possibly become a "Chinese style of oil painting" and integrating it with his generation of artists' reflection of life and concern about society.

Hence, the art of Dunhuang particularly resonated with Chang Shuhong, as it was, in his own words, "created by ordinary people and for the ordinary people". He saw in it exuberant, sincere creativity that he realized would have a significant impact on the creation of art in the coming decades, Zhang says.

Two paintings of fresh produce Chang Shuhong created in different periods exemplify his transformation in artistic style. One was painted in 1933 in Paris, displayed at the Chang Shuhong Gallery, and the other in 1976, on show at the temporary exhibition.

The earlier painting, conforming to the classical style, is overall of a gray tone with low saturation, whereas in the latter one, the painter used bold and clear lines, large red and green blocks to create striking contrast, though like before, the fish glisten in subtle light.

Zhang adds that such transformation reflects the influence of the art of Dunhuang.

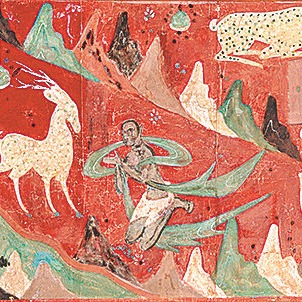

Highlights of the exhibition also include one of Chang Shuhong's facsimiles of a mural from Cave 254, dating back to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534), depicting a well-known piece of the Jataka tales, narratives of former incarnations of the Buddha. In his lifetime, Chang Shuhong copied this mural many times.