Growing a new branch of art in literary soil

By introducing the concept of literati painting, Su Shi changed the landscape of creativity, Zhao Xu reports.

'It took someone as talented and revered as Su Shi to propel Chinese art forward. Anyone other than him would not do," says Pang Ou, ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy expert from the prestigious Nanjing Museum, located in Nanjing city, eastern China's Jiangsu province.

The man Pang was talking about was a prominent figure living largely in the 11th century during the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), a man whose lengthy career in the bureaucracy had brought him inevitable damage and led him to focus more on matters of writing and art, the dual fields in which he has been enshrined.

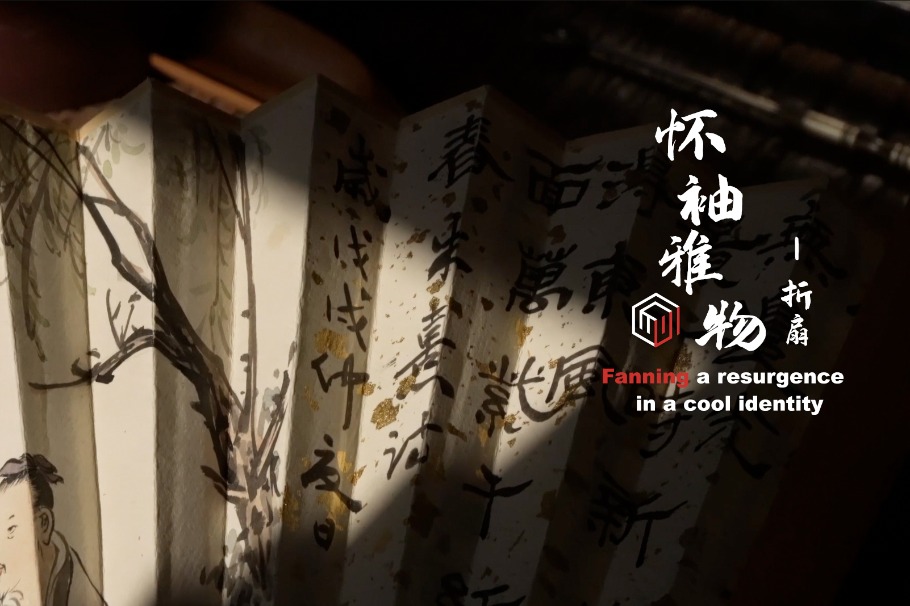

Such was his influence that Pang has decided that a full-blown exhibition, with more than 150 paintings and calligraphy pieces from eight Chinese museums, is what he needs to do the man justice.

"Today we talk about literati painting — the term coined by Su himself to refer to paintings by educated men to convey their inner thoughts, as well as their own state of being — as dominating the history of Chinese art. Yet without Su, the genre, which was also a trend lasting for nearly a millennium, may not have formed until a few centuries later, if it was formed at all," says Pang.

"By saying that you can express what's in your heart through painting, in very much the same way men of words were doing through poetry during his time, Su elevated the former to the same artistic height of the latter.

"Before Su, painting was mainly for decorative purposes, and routinely appeared as frescoes or on folding screens which served as room dividers; after him, painting, done in the spirit and sensibilities of the literati, was an ordained form of high art, a worthy pursuit for anyone who considered himself culturally sophisticated."

So what constitutes a literati painting for Su? The curator attempts an answer with a Su Shi painting that opens the show. It is a simple depiction of two rocks and a few stalks of bamboo, against a misty backdrop of distant mountains and waters. According to Pang, the work was a self-portrait in the metaphorical sense of the words, reflective of how Su saw himself at the end of a long exile, between 1079 and 1084.

Before 1079, Su had had a rather smooth sailing in court politics. Then his detractors pointed at some of his writings and accused him of being scornful of the emperor's reform initiatives. Those men had the emperor's ear, and Su, as a result, was sent to Huangzhou in modern-day Huanggang city of Central China's Hubei province.

"The experience represented for Su a major turning point. For five years, he was forced to reflect, transcribing his thoughts on paper in monumental pieces that we still learn today," says Pang. "It was also in Huangzhou that the man started to truly engage himself with nature, art and self."

The bamboo as rendered by Su sprouted from underneath of the rock to enjoy random growth, a symbol of endurance in face of hardship. The hazy landscape on the background was the Xiaoxiang region in modernday Yongzhou city, Hunan province. A watery patch of land about 600 kilometers from Huangzhou, Xiaoxiang had been known in Chinese history as the land of exile, both forced and self-imposed, where a sense of tragic beauty permeated nature's wilderness.

Su, who once summed up his entire life with the names of the remote locales to which he had been banished — Huangzhou was the first one — was clearly being allegorical, if not sadly prophetic.

The work is considered one of the only two surviving paintings by Su. From there, the show meanders through the ensuing millennium, during which those who came after Su and looked up to him found themselves in comparable situations or sentiments. And they, like Su, turned to painting, the very purpose of which, to quote Su himself, "is not to create a simple likeness, but to help one probe his own thinking and reveal his mind".

This was especially true for those living through the turbulent times of dynastic transitions. One of them was Zhu Da (1626-1705), who had the good luck to be born out of the royal family of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), and the bad luck to witness its fall when he was 18.

Two of his works are on view. In one, bamboo plants grow from behind a rock in front of a window, which in turn frames an interior view comprising a table, a urinal-shaped container and some rare fungus known as lingzhi.

"For all the mythical healing power accorded to lingzhi by ancient Chinese, it has appeared in a urinal, an item associated with filth. That for me was the painter's perception of himself and the world around," says Pang.

That world was a cold one, where all birds as depicted by Zhu had to stand on one foot and keep the other tucked close to the body for warmth. A few of these birds are on view at the Nanjing exhibition that runs till Aug 18.

And warmth was what Su must have longed for when he wrote in Huangzhou in the spring of 1082 that "cold vegetables were being heated in the empty kitchen, by wet reeds smoldering in a broken stove".

"Such misery! Su Shi wasn't born to laugh at the ups and downs of life — no one was. Although his followers tend to forget it, the sense of transcendence exuded by his writings wouldn't have existed without some intense personal struggle," Pang says.

One of these writings recorded the building in Huangzhou of a small dwelling, which Su named "the Snow Hall", before going on to paint its four walls with snowscape.

Pang had the story in mind when he decided to include in the exhibition a painting from an unknown Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) artist that shows towering snowy mountains under a leaden sky. The canvas is occupied on its lower left corner by two scholarly-looking gentlemen sitting inside a thatched hut, and on its lower right corner, by a boatman who, with a pole, is maneuvering himself away from the bank, having enabled the meeting between the two friends.

"Companionship in solitude — that's what the painting was about," says Pang.

Su must have understood this. Two of his most celebrated pieces of prose were written in Huangzhou, at the end of two separate boat trips with friends. (The boat trips themselves were later taken up as a major painting subject, rendered tirelessly by those in awe with Su's talents.)

"The clear breeze over the river and the bright moon amid the mountains ... are the infinite treasures of Nature the Creator, shared in joy by both you and me," he wrote in one of the pieces.

Pang says: "Wu jin zang — that's the Chinese for 'infinite treasure', which gives the title to our exhibition.

"What Su Shi had considered nature was for him, he has been for generations of Chinese."