The Long and colorful journey of enamel

Illuminating Chinese art history with their splendid hues, these wares bear witness to cultural exchanges going back centuries, Zhao Xu reports in New York.

What would be the most apt words to describe the domestic ambience of a literary-minded man living in 14th-century China, during the Ming empire (1368-1644)? To a modernday person who has dabbled in the country's aesthetic history, likely candidates would be "sober" and "demure", bearing in mind the succinct lines and dark colors of the now-hailed Ming-style furniture.

Well, all the writing tables, armchairs and wardrobe cabinets on display in one of the Chinese galleries on the second floor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York prove they would be right.

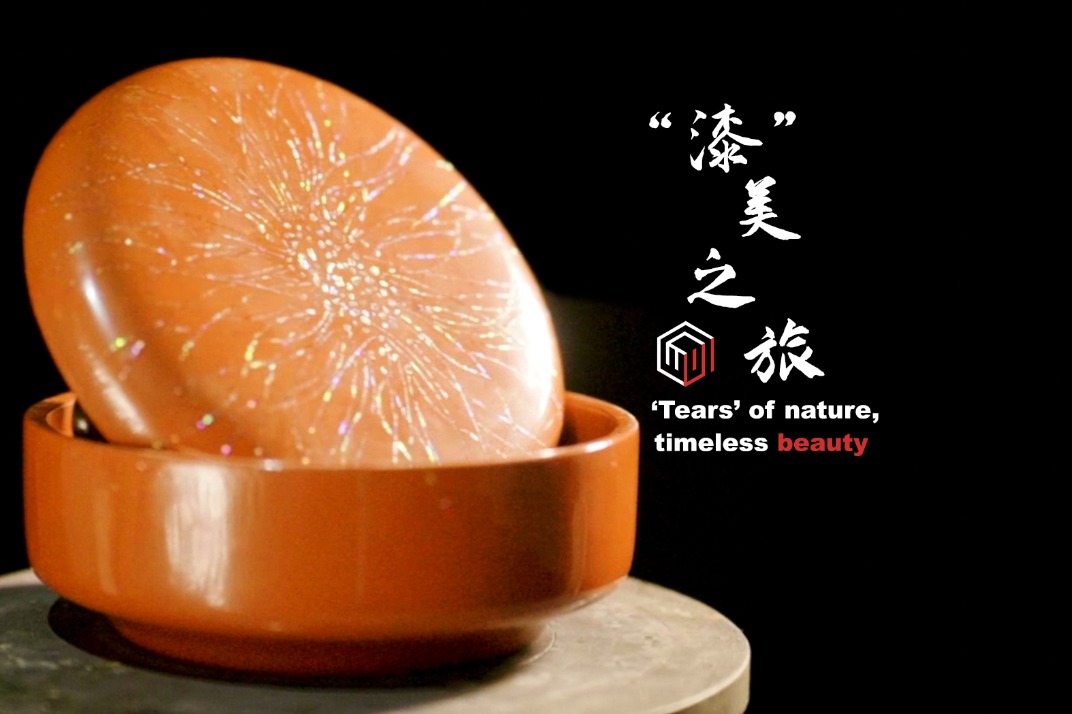

But only partially, says Lu Pengliang, assistant curator of the museum's Asian art department. In a sequestered space on the third floor, Lu has quietly amassed a clamorous show, with nearly 100 pieces of Chinese enamelware, almost all dating to the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. With bold colors bordering on boisterous and patterns intricate to the point of intoxicating, the exhibits, from fruit plates and flower vases to incense burners and snuff bottles, beckon viewers with a flight of fancy into history.

"The sheer number of Ming and Qing enameled wares that have been found and the multitude of purposes they served testifies to their role: people lived with and amid them," says Lu, who titled the display Embracing Color: Enamel in Chinese Decorative Arts, 1300-1900.

The exhibition opens with a prelude, in the form of a bluish-white porcelain vase from around the 13th century. With its swirling carved pattern silenced by a glacial sheen, the vase exudes a calmness and a composure that China's elite literati valued.

"Polychrome porcelain enjoyed an elevated status in Chinese art history for a long time," Lu says, pointing to a collector's manual from the late 14th century, which described cloisonne enamels as "out of place in a scholar's study" for its perceived visual excess.

Yet 68 years later, in a revised version of the book, the new author reversed his predecessor's judgment, calling cloisonne enamels of the imperial court "delicate, sparkling and lovely". What happened in between the two editions was the royal family acquiring taste for color, which in turn led to the new aesthetic's adoption throughout society, Lu says.

"In a sense, it was more about who set the standard for beauty than about beauty itself. This is not to discredit the technical tour de force that had allowed this to happen."

- Christie's Shanghai to showcase two masterpieces for limited time

- Guizhou craftsman brings clay whistle alive

- Calligraphy and Painting Challenge themed on the Spring Festival calls for entries worldwide

- Amazing China in 60 Seconds: Liaoning

- Artworks shown at national academy picture routes to rejuvenation