Saving a tradition of creativity

A millennium-old ceramic variety, which came to global attention when a shipwreck's cargo was salvaged, sheds light on a fascinating period of trade and art, report Wang Kaihao in Beijing and Feng Zhiwei in Changsha.

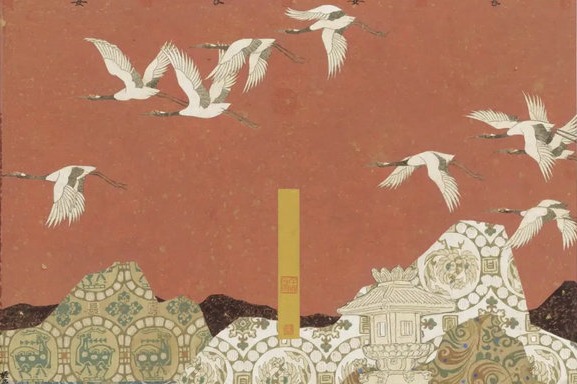

High waves, a perilous, yet lucrative, voyage by a fully loaded cargo boat and an accident that seems too trivial to be documented in the long course of human history. These are the raw ingredients of an intriguing tale. A tale of treasure lost and found but also an insight into a creative era.

The Arabic-style sailing boat may have failed to deliver to the eager and expectant merchants waiting at its destination, most likely somewhere in the Middle East.

No one can exactly say how the ship sank more than a millennium ago, but when the Batu Hitam ("black stone") shipwreck was found in 1998 off the coast of Indonesia, it stunned the world: Its well-sealed hoard offered a startling glimpse into the world of Chinese ceramics during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) — a cultural and social pinnacle during China's imperial era.

More than 67,000 Chinese ceramic artifacts were stored in its hold, and 50,000 of them seemed to originate from the same place, Changsha, the present-day capital of Hunan province. According to UNESCO, the cargo is the biggest single collection of Tang Dynasty artifacts found in one underwater location.

The so-called Changsha wares were produced in the kilns of Tongguan town on the outskirts of that commercial hub.

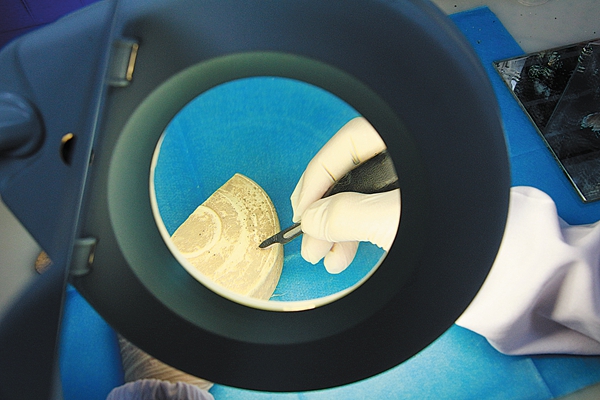

In the past four years, Yang Jinsong, a cultural relic conservator, has been devoted to breathing a second life into the broken shards at Changsha Museum. With his fingers, dozens of pieces of Changsha ware have been reassembled, allowing people to better understand the origin of these Tang treasures from the dust of history.

"A great deal of energy has been spent comparing these pieces and putting them back into their original positions," Yang says.

The biggest difficulty, Yang adds, is restoring the magnificence, splendor and luster to the colors and glaze.

As one of the earliest known ceramic varieties in China to use under-glazed colors, Changsha ware is extremely demanding in its technique. One question has posed a challenge to every restorer: Since the original glaze is formed after being fired in a kiln, how can they re-create the appearance at room temperature?

Adding colors one layer after another requires patience and experience to create the right thickness of glaze to make the restored segments resemble the original.

A database is being gradually established based on archaeological discoveries of Changsha wares. Only digital analysis, scrutiny of earthen bodies, glazing materials, production techniques and other crucial information surrounding the ceramic samples, invisible to human eyes, can offer key references for restoration.

Despite the fact that modern technology may greatly facilitate Yang's job, he still feels like the artisan who first gave life to these exquisite pieces of porcelain.

After all, unlike bigger and national-level museums with much larger conservation squads and more detailed division of labor, only six full-time conservators work at Changsha Museum. Yang and his colleagues have to take care of the whole process, ranging from researching art history, performing chemical analysis, to actually fixing the artifacts.

"On average, fixing one ceramic artifact will take one month," Yang says. "But, if the situation is more complicated, more time is needed.

"Sometimes, you have to consider yourself a doctor," he says.

"A relic is your patient. Your duty is to cure it and prolong its life."

Nonetheless, an almost philosophical question was also raised by conservators: If the porcelain is a patient, should it be given a perfect appearance, just like in its prime?

According to Zhang Xingwei, director of the cultural relic conservation center at Changsha Museum, the basic principles of being "reversible" and "recognizable" are followed in restoration.

"If we figure out we've used the wrong materials, we need to be able to remove them," Zhang says. "Or if we find a better solution in the future, we have to be able to replace the traces of our current restoration."

In the gallery of Changsha Museum, some broken porcelain wares are also on display.

"Our mission is to maintain their health and keep them 'alive' as long as possible, rather than giving them an impeccable appearance," Zhang explains. "It's also a way to show people their past."