Books that speak volumes

By accident or design, many missionaries who came to China from the late Ming to the early Qing dynasties, acted like Marco Polo in reconnecting the cultural knots between East and West that had been cut off for centuries following the wane of the ancient Silk Road.

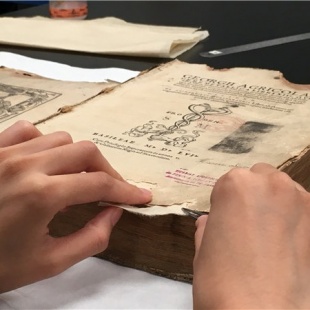

One essential task in such cross-cultural communication would have been compiling bilingual and multilingual dictionaries, some of which are on display in the exhibition.

The difficulties that the French Sinologist Alexander de la Charme would have had to overcome as he wrote a French-Chinese-Mongolian-Manchu dictionary from 1758 to 1767 are barely imaginable.

The 17th-century Italian missionary Basilio Brollo de Gemona spent 24 years in China and com-piled a Chinese-Latin dictionary.

"Among the dictionaries Western missionaries compiled in those days, this is without doubt the best bilingual one," Zhao says. "However, one drawback is that it is extremely heavy, needing two people to carry it."

Westerners' knowledge of China also improved greatly in this multicultural interaction. As modern cartography began to make its mark, Chinese maps began to resemble those that we see today, says Weng Yingfang, a librarian in charge of Western map studies at the library.

She singles out Martino Martini's Novus Atlas Sinensis (new Chinese atlas), printed in Amsterdam in 1655.

"It's the most authoritative reference in the Western world then relating to Chinese geography. It's based on his travel all around the country."

However, in the atlas the Great Wall is located much further north than it really is, and some researchers have postulated that Martini, who lived in southern China, in fact never had any firsthand knowledge of the wall.

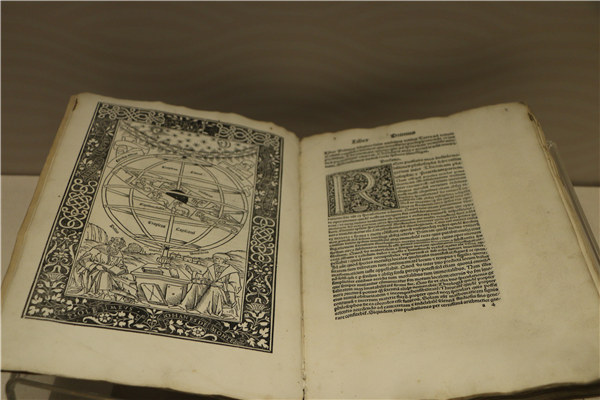

The exhibition depicts works related to early modern technology as well as anatomy and mathematics being introduced to China by means of Chinese-translated versions of original works of the time, and in the other direction Chinese philosophy and history were widely promoted in Europe.

For example, Confucius Sinarum Philosophus (The Chinese philosopher Confucius), printed in Paris in 1687, was the first comprehensive writing on Confucianism in Europe.