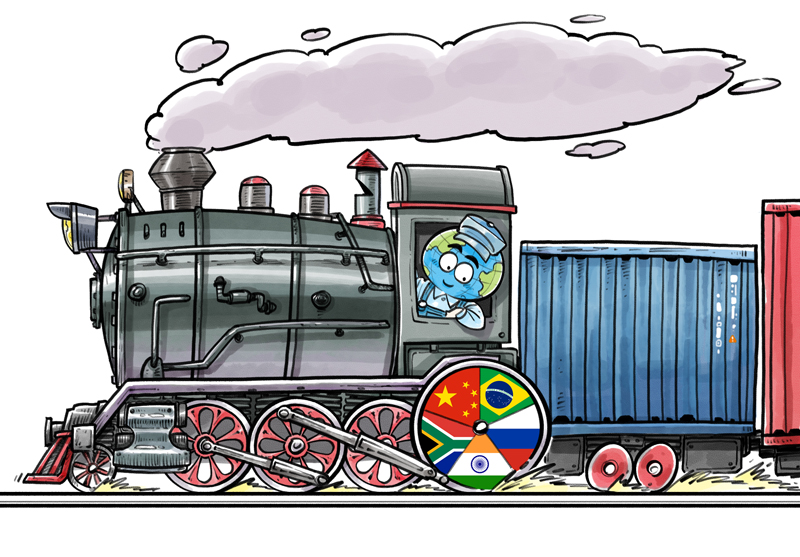

Tariff war doesn't dampen BRICS' future

The five members of the group should pursue more free trade among themselves to render the US trade policies less relevant to any of them or, for that matter, the rest of the world

This autumn will be the 17th anniversary of the BRIC acronym, which I mentioned in an article titled "The World Needs Better Economic BRICs". I laid out different scenarios, as to how Brazil, Russia, India and China could grow over the decade from 2001 to 2010, and as a result of this, how global economic governance needed to be changed. That was nearly 17 years ago.

What has happened since, both to their growth performance and that of the world, and what has happened to world governance, and what is the future, especially for the BRICS economies, with now a capital "S" to include South Africa?

Of course, all these questions come against the background of the forthcoming meeting of the political leaders of the BRICS nations, indeed, their 10th such annual meeting.

Of course, in the middle of the past 17 years, in the autumn of 2008, we experienced the global financial crisis, which led to the subsequent sharp slowdown in the world economy, and in many ways, the 17 years can be characterized as two distinct periods, extremely strong growth across a large part of the world before the crisis, and not so impressive growth post crisis. At least, this is the superficial appearance, as well as the observation of so many so-called experts.

In fact, while global GDP growth has been about 3.4 percent so far this decade since 2011, and despite being lower than the 3.7 percent of the previous decade, it is about the same as the growth experienced during the 1980s and 1990s. While global GDP growth has been a bit weaker, it hasn't weakened as much as many believe and when you delve into the regional details, there is one reason, and it is called China. The ongoing rise of China, despite its own slowdown, continued to be a significant source of strength for the world economy, never mind for the BRICS group alone. And of all the increase in the global US dollar nominal value of GDP this decade, nearly 50 percent of it has come from China alone.

Within the BRICS aggregate, in many ways, the most powerful fact 17 years later is just how dominant China has become. The BRICS acronym is occasionally criticized for the inclusion of various countries, and sometimes for the exclusion of others, neither of which makes sense to me-with the possible issue of South Africa. The reality today is that the size of the Chinese economy is $12.7 trillion, which is more than double the rest of the BRICS economies put together. It creates another South Africa every three or four months, and perhaps another Russia every year. It is not far off being six times bigger than India even though India is now growing at a stronger rate of GDP.

This reflects the fact that since 2001, China has grown almost as strong as the more optimistic scenarios I envisaged, and not withstanding annual ups and downs, and all its domestic challenges, the Chinese economy remains on course to become as large as the United States' sometime between 2025 and 2030, and because of this, and its dominance, the aggregate of the BRICS economies remains on track to become as large as the G7 collectively sometime between 2035 and 2040.

Despite slowdown, China's economy can match the US'

In this regard, China is likely to experience slower economic growth in the next decade, and this shouldn't be a surprise to anyone, and certainly wouldn't be to me, and crucially, I have anticipated softer growth, probably between 5 percent and 6 percent, and still become as large as the US in economic terms by 2027. If the Chinese economy doesn't slow down, it is likely to match the US' sooner.

Long-term growth for any country is primarily driven by two factors: its workforce and its productivity. China has reached the stage when its demographics are such that its workforce, if not having peaked already, is close to it, so the only way it can continue to grow more than 6 percent is through very strong productivity growth. In this context, the dramatic appearance of a tariff war, initiated by US President Donald Trump, could weaken China's growth rate further.

However, so long as the tit-for-tat battles now taking place are contained, in my view, there could be some side benefits for China's long-term growth performance, as it is likely to encourage a faster pace of domestic economic reforms, which is much more important to China's productivity challenge relative to its external trade performance.

China continues to be at the center of the more positive aspects of world growth opportunities, and the rise of Chinese consumers is probably the single most important development in the world economy, something US policymakers would be wise to take more care to notice.

As for the other BRICS members, they face different growth prospects and challenges.

India has the most powerful labor force dynamics, and it is currently in the sweet spot of rapid labor force growth and starting to experience some of the intensity of urbanization that China has experienced the past 20 years. It can therefore easily experience real GDP growth rates of more than 7 percent through the next 10 years, and indeed, if it adopts more significant structural reforms, it has the potential to grow as much as 10 percent. By the middle of the next decade, India should easily have become the fifth-largest economy in the world, if not already challenging Germany for the fourth largest-and it remains on track to become the world's third-largest economy by the late 2030s.

Brazil, Russia and South Africa face a common challenge

As for the other three BRICS members, Brazil, Russia and South Africa, while they are very different economies and societies, they each face a very big, common challenge-they are highly dependent on commodities, and their volatile cycles. In my view, in the long term, they are being held back by excessive dependence on commodity price cycles. As we have seen over the past 17 years, especially with Brazil and Russia, everything appears to be fabulous when commodity prices are rising sharply, but when that inevitable period appears, and commodity prices drop sharply, their economies suddenly appear to be full of weaknesses. The same pattern is true for South Africa, but to add to their woes, they have a much smaller working population, quite worrying education and health challenges, and need major structural reforms.

I never included South Africa as part of the BRIC group, because it is very small, and there are lots of other countries, including Nigeria, which would have at least as much justification for being part of the group. And I cannot imagine in the next 20 years South Africa being among the world's biggest 20 economies. Brazil, however, despite its weakness of recent years, is still either eighth or ninth largest, and Russia is possibly 11th largest. Both can credibly become much larger, with Brazil especially supported by reasonable demographics. But they each need to pursue policies to rid themselves of the so-called commodities curse, and make their economies more resilient and dynamic.

It is in this context, the leaders at the 10th BRICS summit should ask themselves what we can do to boost our collective growth performance. There are many things, and of course, one especially attractive one in the context of the US-driven tariff wars, that the BRICS members should pursue, that is, more free trade among themselves, which would render the US policies much less relevant to any of the BRICS members or the rest of the world.

The author is former chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management and a British economist best known for coining the term "BRIC". He contributed to this article to China Watch Institute, a think-tank platform powered by China Daily. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Watch.