Art has prospered in era of reform

Artists embrace opportunities to collaborate and share ideas with others around the world

Chinese artists saw the reform and opening-up of the Chinese economy in 1978 as an opportunity to open up Chinese artistic expression and import new ideas and techniques from abroad.

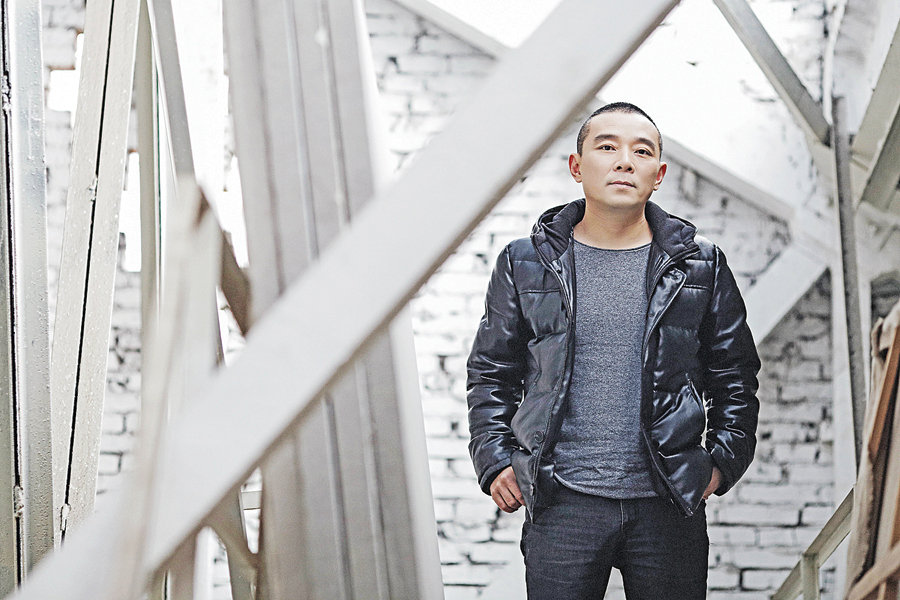

Zhu Jianhui was one of those artists working in China at the time of the new reforms.

Zhu, from Jiangsu province, said Deng Xiaoping’s new policies brought, “unprecedented opportunities for China’s artistic development and exchanges with other countries”.

He noted that, with more than 5,000 years of Chinese history, this “long-standing culture and art should belong to the commonwealth of all mankind”.

“The reform and opening-up provided opportunities for collaboration between Eastern and Western arts, which has enriched Chinese arts,” Zhu said. “It gave Chinese artists a greater chance of accepting art and artists from all over the world. The artists have increased their cultural self-confidence and found the direction of exploration, mutual benefit, and common development.”

Some experts believe the Chinese contemporary art movement began emerging before Deng’s reforms.

As the “cultural revolution” (1966-76) ended, some artists on the Chinese mainland began to experiment with, and embrace, the modern art movement.

For Zhu, Deng’s policy allowed him to expand his horizons and encouraged him to “appreciate foreign art”.

Paul Gladston, a leading expert on Chinese contemporary art and culture, said: “Reform and opening-up was a significant shift for art in China, but we need to avoid thinking of it as the only factor that changed things, even before reform and opening-up, there were significant changes in China.”

Gladston pointed out that even before the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, there were multiple new art movements in China. Movements continued throughout the 1960s, 70s and 80s.

Groups such as one known as the Stars held an unofficial open-air exhibition that took place less than a year after the 1978 opening-up policy.

And more artists gained control over their creativity, which led to an avant-garde movement.

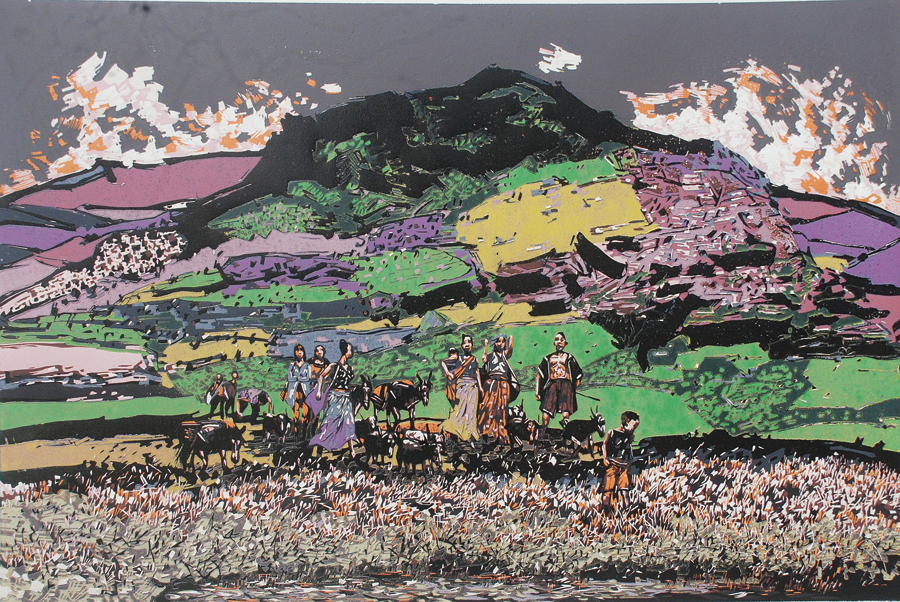

He Kun, regarded as a leading exponent of reduction woodcut art in China, said he would not have had the artistic achievements he has had if not for the policy.

“I study and use forms of Western art,” he said. “By using the Chinese techniques I’m familiar with, I approach my work from another cultural perspective.”

He said the opening-up policy had a “great influence” on his art and has allowed the world to understand Chinese art.

Gladston noted that, although the reform and opening-up policy wasn’t aimed specifically at culture, it did open up circumstances that are “conducive to the development to the kind of contemporary art we now see in China”.

By the late 90s, Chinese contemporary art had gained recognition and market value, both domestically and internationally, but it wasn’t until the early 2000s that the art world caught onto what Chinese artists were doing and the art was accepted into the mainstream.

Many headed West with the aim of breaking free from the conventions of the traditional ink paintings that were often linked with Chinese art and artists.

Gladstone said: “There has been a historical tendency for international Western audiences to stereotype Chinese art. They see it as a kind-of non-changing repertoire of ink painting, shanshui.”

Yang Qi, a 66-year-old from Wuhan who is now based in Germany, said: “Europe has gone from impressionism, cubism, modernism, postmodernism, to contemporary art in nearly 200 years. In the last 30 years, China continues to experiment with contemporary art and a lot of work still needs to be done.”

Jiao Xingtao, vice-president of the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, believes that, since 1978, the themes of artistic expression have become more abundant and free.

Jiao said Chinese art and the creation of contemporary art has integrated into the world and “Chinese art has started to draw worldwide attention with its unique charm”.

As well as promoting Chinese art, Jiao said dialogue and communication is even more important.

“Chinese art needs to establish its own methodology and values based on its own history and today’s social practices,” he said. “The creation of contemporary Chinese art, like contemporary Chinese culture, has spontaneous and strong vitality and creativity.”

As China continued to open up, collectors and galleries have taken interest in Chinese artists.

In the UK, groups such as ArtChina and Sino European Arts promote Chinese art.

“Contemporary Chinese art is, in short, now a major force culturally, financially, and politically within and outside the PRC,” Gladston said. “As such, it can be understood as a significant modernizing shift in artistic practice and as indicative of a wider transformation of society and politics within the PRC.”

More Chinese contemporary works are being displayed around the world.

“What we could identify with as contemporary art in China is artists bringing together aspects of Chinese cultural identity and tradition with techniques and attitudes that we associate with modernist and post-modernist art in the West,” Gladston said. “This arguably includes contemporary reworking of traditional Chinese ink painting.”